Cheesemaker sees red

David Birchall examines a recent decision regarding specifying colour elements of marks. [2019] EWHC 3454 (Ch), Fromageries Bel SA v J Sainsbury plc, High Court, 12th December 2019

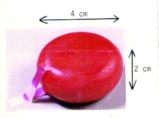

In 1997, Fromageries Bel SA (FBSA) obtained a UK trade mark registration for which the following description was entered on the UK IPO’s register: “The mark is limited to the colour red. The mark consists of a three-dimensional shape and is limited to the dimensions shown above”.

In order to be registrable as a trade mark, a sign must, under s1(1) and s3(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (the Act), be capable of being represented in a manner which enables others “to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to the proprietor”.

Invalidity action

J Sainsbury plc (Sainsbury’s) applied to invalidate FBSA’s registration on the basis that, inter alia, the mark did not satisfy the requirements of s1(1) of the Act because the phrase “the colour red” in the description did not provide sufficient clarity and precision.

The Hearing Officer (HO) considered the Sieckmann criteria1 and then assessed the essential characteristics of the challenged trade mark. The colour red was found to be an essential characteristic.

The HO agreed that there was scope to question whether the protruding parts of the cheese casing qualified under the description “red”, but ultimately accepted that they did.

Next, the HO considered whether the colour red was defined with sufficient clarity and precision, referring to the judgment in Libertel2 and the practice of using recognised colour identification codes. The HO opined that the Libertel requirements apply to all marks for which colour is an essential characteristic.

The HO considered three alternative sources for the primary indication of the subject matter of a trade mark: (i) the written description; (ii) the picture; or (iii) neither. The HO held that “the colour red” wording did not satisfy the Libertel requirements.

The HO also held that the absence of colour identification codes in FBSA’s registration meant that the colours were not represented in an objective and durable manner. On this basis, FBSA’s registration was declared invalid.

Basis of appeal

FBSA appealed the invalidation decision, arguing the following three separate bases:

(i) the Sieckmann criteria should be applied in a different way depending on the type of mark (for example, the colour in a mark like FBSA’s might not need to be defined with as much precision as in a registration of a colour per se);

(ii) not interpreting the mark as being limited to the pictorial representation was an error; and

(iii) FBSA should be allowed, under s13(1) of the Act, to limit the rights conferred by its registration to Pantone No 193C.

FBSA filed new evidence, including evidence of many other registrations on the UK IPO register which it argued must necessarily be likewise invalid. Sainsbury’s challenged the admissibility of the new evidence but the Court ultimately agreed to it being introduced.

FBSA argued that there are two types of colour mark: one where the colour is the only essential characteristic of the mark and another where it is not. The UK IPO wrongly categorised the mark as belonging to the first category, FBSA argued, explaining that the colour red was not the only essential characteristic of the mark and therefore it did not need to be defined with such precision.

The Court held that there was a connection between the Sieckmann criteria and the requirement that the mark be capable of distinguishing the goods of one undertaking from those of another. It determined that use of a colour code is liable to assist not only in meeting the Sieckmann criteria but also in ensuring that the mark is capable of distinguishing goods.

The Court picked out two registrations from the list of UK registrations, all of which FBSA argued would be invalid on the basis of the decision under appeal. One was a stylised version of COCA COLA and the other a stylised version of TESCO. The description of the former mark is: “the applicant claims the colours red, silver, white and yellow as an element of the mark”. The description of the latter mark is: “the applicant claims the colours red and blue as an element of the mark”. The Court held that the precise hue would be unlikely to play a significant role in either of these marks’ capacity to distinguish and that a variation

of the hue would not necessarily affect their ability to distinguish.

The Court held that the real question was whether FBSA’s mark was capable of distinguishing FBSA’s cheese from the cheese of others if the hue used is any hue of red which FBSA choses to use from time to time. On this point, the Court concluded that, on the balance of probabilities, FBSA’s mark could only be capable of distinguishing if a specific shade of red used on the main body of the products is associated with FBSA’s cheese. FBSA’s first ground of appeal therefore failed.

The Court also rejected the second ground of appeal – that the registration should be limited to the pictorial representation provided.

In relation to the third ground of appeal, the Court referred to the 2004 decision regarding an application to register the three-dimensional shape of a Polo mint, in which it was held that it was not appropriate to introduce colour-related details which would make a mark distinctive and registrable via a limitation under s13(1) of the Act. The Court agreed with the finding in that case that there was an important distinction between a limitation which narrows the scope of acts that would infringe a trade mark and a limitation that would affect the description of the mark itself.

The Court held that limiting the colour of FBSA’s registration to Pantone 193C would not simply limit the rights conferred on FBSA under s9(1) of the Act but would affect the description of the mark itself. On this basis, the Court refused FBSA’s request to do so. The appeal therefore failed in its entirety.

The decision is a reminder of the advisability of regularly reviewing the validity of trade mark registrations in the light of clarifications provided by case law.

1 Sieckmann v Deutsches Patent und Markenamt (C-273/00)

2 Libertel Group BV v Benelux – Merkenbureau (C-104/01)

Key points

There is no rule that the pictorial representation of a mark takes precedence over a description

Under s13(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, the owner of a mark can agree to a specific limitation

Amendments cannot be made to the description of a mark through a limitation