Brand strategy: Revolution = Evolution

Adjoa Anim reflects on the historic wave of brand rethinks following recent anti-racism protests.

George Floyd’s brutal and very public death while being detained by Minneapolis Police forced the issue of racial justice and inequality to the fore in a world stilled by varying degrees of COVID-19 lockdown. The difficult conversations and protests that followed presented an added challenge to some businesses that were already under strain.

Brands with racist, colonial and oppressive origins had long been the subject of complaint for those in the know. But these explosive events exposed them to a larger section of society, and the resulting protestations pushed businesses in fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), entertainment, sport and professional services to respond by announcing changes to their brands.

One such product was the Fair & Lovely line of beauty products, which has been sold in India and Bangladesh for many years. Hindustan Unilever Ltd changed the name to Glow & Lovely and Glow & Handsome, in an effort to move away from any association with “the benefits of fairness, whitening and skin lightening”. This met with some disapproval because the nature of the product’s aim – which was seen as promoting colourism – remained unchanged. Currently, Unilever’s website declares that its latest formulation aims to “enhance radiance and glow holistically” and insists that “the product has never been, and is not, a skin bleaching cream”.

Similarly, last summer, L’Oréal announced plans to remove references to “white/whitening”, “fair/fairness” and “light/lightening” from its products. Model Munroe Bergdorf criticised the announcement on the back of claims that the company had fired her from a central role in a product campaign in 2017 after she spoke out against racism. L’Oréal has since apologised for its handling of that earlier situation, rehired Bergdorf and invited her to sit on the company’s UK Diversity and Inclusion Board.

Other FMCG products under review include Darlie toothpaste, sold in Asia. Perhaps unbelievably to UK readers, the product was originally called Darkie, a widely recognised racial slur used against African Americans in the 1930s. Even today, the product’s Chinese name translates as “black person toothpaste”. Earlier versions of the branding featured a representation of a minstrel-show character, and the current image of a smiling man in a top hat is being reassessed to address negative racial stereotypes.

In the food and drink sector, we’ve seen Mars scrap the name and image of a fictional black rice farmer that featured in its Uncle Ben’s rice brand – a brand identity that dated back to 1946. The new name, Ben’s Original, will appear on packaging from 2021 alongside new imagery, in a bid “to create more equitable iconography”. The company has also announced various new initiatives to support African Americans and other underserved communities. And just as Mars made its statement, The Quaker Oats Company also announced a review of its Aunt Jemima line of syrups and foods, a 130-year-old brand featuring an African American woman named after a minstrel-show character.

The names of these products were rooted in a history of white Americans addressing elderly African Americans as “aunt” and “uncle”, as they were deemed undeserving of “Mister” or “Miss”. The Aunt Jemima character was also considered to be reminiscent of the “mammy” figure, a black woman content with her lot in life, which consists of serving her white masters. Also under review are ConAgra Brands’ Mrs Butterworth’s line – the firm acknowledging that its “loving grandmother” may not be viewed as intended – and B&G Foods’ Cream of Wheat porridge brand, the identity of which was based on a caricatured Chef Rastus character.

Indigenous iconography

Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream’s Eskimo Pie brand has also been revamped. The packaging of Eskimo Pie products has long featured an image of a boy in winter clothing. “Eskimo” is in fact a derogatory term first used by colonisers of the Arctic region, meaning “eater of raw meat”, implying barbarism. Products renamed “Edy’s Pie” – honouring one of the company’s founders – are expected to hit shelves by 2021.

Meanwhile, Nestlé SA has publicised plans to rename its Colombian Beso de Negra brand (which translates as “kiss from a black woman”) and its Australian Red Skins and Chicos confectionery lines, the latter two being derogatory terms for Native Americans and people from Latin America respectively.

On the entertainment front, UK record label One Little Indian Records changed its name to One Little Independent Records and dropped a logo that, according to its announcement on Twitter, “perpetuated a harmful stereotyping and exploitation” of Native Americans. The company also made a series of donations to charities supporting indigenous peoples and populations.

Not all changes of name have gone so smoothly, however. US country band Lady Antebellum announced a change of name to Lady A in June. “Antebellum” describes the pre-Civil War period and architecture of the southern US states, closely associated with the slavery era. There had been historic use of the name Lady A by the band and fans, and the band owned three US registrations from 2010, covering classes 9, 25 and 41. It also filed a new class 35 US application a day before the announcement. Shortly afterwards, a Seattle-based blues, funk and soul singer, Anita ‘Lady A’ White, stated that she had used the name for 20 years. Initial attempts to settle the matter descended into a legal dispute that has been rumbling on for months.

The Chicks, formerly The Dixie Chicks, had a happier experience, having jettisoned the “Dixie” element and its association with the Confederate states that supported slavery. The band stated that it is co-existing with a New Zealand-based duo of the same name.

Individual artists have made changes too. UK DJ Joey Negro announced that he would use his real name, Dave Lee, a day after US DJ The Black Madonna publicised her name change to The Blessed Madonna, in response to a petition. Both artists made references to the unacceptable and controversial nature of their names and a desire to drive change.

Teams in trouble

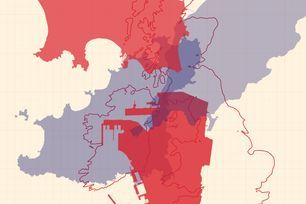

The names of some North American sports teams have been bones of contention for decades. A notable example is the NFL team the Washington Redskins, which adopted its name in 1933 and a logo featuring the side profile of a Native American in 1937. Indigenous groups have been protesting against the “Redskins” name since the 1960s, but the cause received more public attention in the 1990s, to no avail. Despite the derogatory nature of the term “redskin”, the owners, management and many supporters were in favour of the name and its associated imagery, considering it a way of honouring Native Americans. After a fresh wave of objections this summer, including from major sponsors such as FedEx and Nike, a temporary name change to the Washington Football Team was announced. The search continues for a new permanent identity.

The Cleveland Indians baseball team launched a review into its name, reportedly to “embrace their responsibility to advance social justice and equality”. In 2019, the team dropped the Chief Wahoo logo from its uniform.

Likewise, Canadian football team the Edmonton Eskimos recently announced plans to drop the “Eskimos” element after three years of consultation. In February, the team had announced that there would be no change (on the grounds that there was no clear consensus from discussions with Inuit groups in northern Canada), but by July calls for change had been renewed, including complaints from the team’s major sponsor, Belairdirect.

Whether other teams will follow these examples remains to be seen. The Atlanta Braves and the Kansas City Chiefs, at the time of writing, were not considering a change, while the Chicago Blackhawks issued a statement to defend the use of their name. In the UK, the Exeter Chiefs Rugby Union team decided to keep its name and logo – use of which was deemed “highly respectful” – but to retire its mascot, Big Chief. The team officially adopted the name and logo, containing a representation of a Native American, in 1999 but claims that the name refers to aspects of Devon life in the 1900s.

Public scrutiny

French advertising agency Rosapark, owned by three white men, announced a rethink of its name after criticism of its use of the name of civil rights activist Rosa Parks. In historic interviews, the owners indicated that the company was in fact inspired by parks in the sense of green spaces, and a “feminine softness”. However, the eight-year-old agency has apologised for any offence caused by any other interpretation of the name.

This metamorphosis appears to have affected public institutions too. In June, Gina Raimondo, the Governor of Rhode Island, issued an executive order to change the name of her state on official websites and documents from “Rhode Island and Providence Plantations” to “Rhode Island”, due to the full name’s association with slavery. The state’s voters then agreed to change the name officially in November.

One rebrand that did not go smoothly was the Berlin Transport Authority’s attempts to rename Mohrenstrasse (“Moor Street”) Metro Station as Glinkastrasse, after it came to light that the new station’s namesake, Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, was anti-Semitic. “Moor” is a medieval term used to describe people from North Africa. The Berlin-Mitte District Assembly recently approved a change of name for the street itself to Anton-W-Amo-Strasse, after Anton Wilhelm Amo, the first scholar of African descent to attend a European university. It is now hoped that the Metro station will follow suit.

Act fast, but smart

As some of these recent examples illustrate, when it comes to addressing cultural concerns, companies may,

understandably, want to react quickly and decisively. However, knee-jerk actions can create problems of their own. The key message is to be thorough and give the work the time it needs. For example, businesses may announce plans for a review in order to respond to social movements but then take time to select a suitable replacement. Once the new mark is selected and publicised, ample time must be given to transition to the new version and iron out any unforeseen issues.

There are a number of other important considerations to take into account too. For example, the importance of searching, for both registered and unregistered rights, is manifest in the Lady A dispute. It would be prudent to have a back-up mark in mind in case an unexpected issue crops up with a proposed replacement.

It is also vital to scrutinise suitability beyond availability. Carry out rigorous reviews to see whether the new mark is globally sensitive. Have the marketing and sales teams speak with local partners to gain perspectives that may be lost to those at head office. This information is invaluable and should be fed back to the brand protection team to help whittle down the choices. Where there is a conflicting right, try to acquire it or agree co-existence before publicising the rebrand, as The Chicks appear to have successfully done.

Keep your options open

Mars filed the first application for BEN’S ORIGINAL in Jamaica on 15th July, nearly three months before it publicly confirmed the new name in September. If businesses have the budget to file applications for several options while completing searches and then follow up with convention priority filings for the selected mark, they can do so and simply abandon the unsuitable marks at later date.

Businesses should think about how to manage the IP connected to the existing brand. Consider whether historic goodwill, reputation and/or evidence of use can support the new iteration. This depends on how far a new brand departs from the old. Land O’Lakes Inc. rebranded in February, for its 100th anniversary, by removing the image of a Native American woman from the packaging of its butter products. It is likely that the company considered how to keep some of its historic evidence for future enforcement and maintenance of its rights.

Balance the cost-effectiveness of abandoning applications and allowing registrations for the existing brand to lapse against the strength of a bold statement of severance by actively withdrawing and surrendering them. The latter may endear businesses to a socially conscious customer base but will cost money. For big corporations, this may be a unique way to bolster customer loyalty and win new business. The maintenance of these rights should also tie in with the length of the transition period before the new brand is launched.

Consider also how to conclude any pending conflicts based on the old rights. Even if there is legal standing to consider in continuing such actions, it may be unpopular to maintain them when a decision has been made to eschew a brand.

Bring everyone on board

Importantly, inform the public of the reasoning behind a change. Consumers appreciate brands that have stories to tell. However, many will be against the change. For instance, plans for Darlie toothpaste faced a backlash against political correctness among some Chinese customers (although it is very likely that these criticisms were based on the lack of awareness around the racist roots of the brand elements).

The family of one of the actresses who had portrayed Aunt Jemima asked The Quaker Oats Company to reconsider the rebrand, as it was part of their family history. These complaints, along with criticisms of “wokeness”, show that businesses may still face an uphill struggle in encouraging some members of the public to accept the changes.

Companies should prepare a strategy for educating customers on the evolution of the brand, including addressing their unacceptable roots. It will be uncomfortable and upsetting, but once brands acknowledge the background of these brands and explain them to consumers, it may convince more people to accept the changes.

Having secured buy-in at board level and educated their consumers, companies must not neglect to take rigorous action when it comes to staff and trading partners. If not, mixed messages can cause damage to the new brand.

A step up for society

Of course, the type of brand changes that we’ve mentioned will not, on their own, get rid of prejudicial attitudes and discrimination. And it is important that we do not completely erase these cultural elements where they can serve as useful reminders of what was deemed to be acceptable at a certain time, showing us the path we’ve taken. This is another reason why it is vital for brands to acknowledge their history when publicising the new iterations of their brands.

Such efforts and acknowledgements of harm will go some way towards promoting a continued and ongoing questioning of any long-standing icons that reinforce persistent stereotypes. After all, studies by academics who examine the interplay between the law and social sciences show that brands play a significant role in shaping individual and group social identity. As a result, it is to be hoped that eliminating imagery that portrays people of colour or indigenous people in a negative light will help to shape a more inclusive and equitable society going forward.