Spot checked

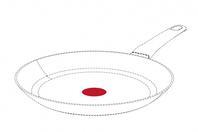

Sophie Soeting considers why a familiar red mark was refused registration. O/587/20, TEFAL (Device Mark), UK IPO, 23rd November 2020.

The UK IPO has denied registration for Tefal’s “red dot” mark, featured in the middle of its cooking pan products, due to lack of distinctiveness under s3(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA). Tefal failed to convince the Hearing Officer (HO) that the dot had acquired distinctiveness, despite a UK high street survey which suggested that 60% of those polled would associate it with the company.

On 17th December 2018, Tefal applied to register a trade mark application for the following goods in class 21: frying pans, saucepans, casserole and stew pans, cooking pots, crêpe pans, grills and woks. The application was accompanied by a written description stating that the mark was a position mark and further clarifying that the dotted lines on the drawing were not part of the mark. The examiner objected to the mark on the basis of s3(1)(b) TMA, noting that the relevant consumer would not attribute trade mark significance to a plain red circle, so the mark was deemed to be devoid of distinctive character.

In response, Tefal sought permission to conduct a survey, involving 250 interviews in high streets across the UK. The examiner stated that Tefal must decide for itself what type of evidence to submit to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness and did not comment on the survey questions proposed by Tefal. In the decision, the HO suggested that, including in ex parte matters such as these, there should be an opportunity for a party wishing to adduce such evidence to be able to discuss it with an examiner or HO (on a provisional and informal basis).

Unusual turn

In a slightly unusual turn of events, shortly after the application was refused and Tefal requested a full statement of reasons for the decision, the HO retired. Tefal was subsequently offered the opportunity for another hearing before a different HO or for the

retired HO to write the full decision. Tefal acknowledged that it had made all the arguments it wanted to in support of the case and it was content for the retired HO to write the decision. However, in this event, it was a different HO who wrote the full decision. As a result, the HO quoted at length from Tefal’s submissions in the decision to avoid any possibility of unfairly paraphrasing Tefal, or not recording them at all.

The HO stated that, while not “banal”, the mark consists of a feature of the appearance of the product concerned: a feature of a certain colour, proportion and position, being plainly visible within the overall shape of (any) pan. Further, it was questioned whether the red dot was independent from the pan, noting that the relevant consumer may not identify the feature as a trade mark in and of itself. As a result, the mark could not perform the essential function of a trade mark.

Survey impact

It is well known that it can be challenging to devise a survey that will effectively demonstrate acquired distinctiveness. Applying the principles established in KitKat1, while the initial recognition figure was undoubtedly statistically significant, the HO concluded that the survey evidence failed to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness. The evidence only went to the question of recognition and association with Tefal, and not to the material perception of the use of the red spot as a trade mark.

Tefal sought to distinguish KitKat, arguing that its mark had been in use in the manner applied for for a number of years, whereas in KitKat the mark had not been used in the form applied for, as it was inside a wrapper and not visible at the point of purchase. However, the HO referred to the core underlying rationale of KitKat, namely that the Applicant had used the sign applied for as a trade mark.

In support of this argument, the HO referred to an “illuminating passage” in the Birkenstock sole mark case2 and stated that it was perfectly legitimate to ask an applicant “what measure, if any, of ‘trust’ or ‘confidence’ it has placed in its sign, such that it has educated the public to it being a guarantee of origin”. Here, he concluded, the main brand was clearly the word “Tefal”, and the red spot was merely a “sub-brand”. It was appropriate to consider to what extent had Tefal had used and promoted the red dot mark over and above its role as a mere feature of the product itself – ie, showing confidence in its sub-brand. The HO concluded that it was difficult to see how Tefal might have shown that kind of confidence in the red dot mark from the evidence provided.

He suggested that while this did not necessarily require independent use of the red dot, “confidence” could have been shown if there were evidence demonstrating, for example, reference to “The pan with the red spot”, other than as a simple feature, or as he suspected, as a technical feature of the pan (to show when the pan is hot enough).

This approach demonstrates that there could be the potential for sub-brands – not those considered to be the main mark of the brand indicating trade origin – to obtain trade mark protection through use in the marketing of that sub-brand.

In relation to the additional evidence provided by Tefal, the HO acknowledged that the sales and promotional evidence provided were substantial.

1 [2017] EWCA Civ 358, Société de Produits Nestlé v Cadbury UK

2 BL O/072/18, para 31

Key points

- Carefully consider the format and probative value of survey evidence given the challenges involved. It may

- be appropriate to seek informal guidance from a Hearing Officer

- When designing marketing materials, IP strategy should always be taken into consideration, particularly if the advertisements would be required as evidence of use to secure trade mark protection

- A key question is: Does the proprietor trust a sub-brand to convey an origin message, and is this apparent in the proprietor’s marketing?

Sophie Soeting is a Chartered Trade Mark Attorney and Associate at Mishcon de Reya LLP

Read the magazine