You know it makes sense

It doesn’t take huge adjustments to make colleagues on the autism spectrum more comfortable, shares Chris Clarke from Vectura Ltd. This article has been republished from the February 2020 issue of CITMA Review.

Imagine that a work colleague comes up to you and says: “There is something that we need to talk about right now.” From the words alone, you can’t tell whether this is a good something or a bad something. But you would probably pick that up from the context, tone of voice, body language, etc – in fact, it has been said that as much as 90 per cent of communication is non-verbal.

Now imagine that you found a piece of paper on your desk saying the same thing. This time you have no cues to help you understand the context. A natural reaction would be to worry that you had done something wrong. You might find the situation quite stressful. This latter scenario illustrates what life is like for many people on the autism spectrum (AS), because they miss out on much non-verbal communication.

This is just one of the points made during an IP Inclusive webinar, which also discussed what it means to be on the autism spectrum and what you can do to ensure your behaviour and workplace enables inclusion of AS colleagues. At the event, Katy Samuels, Employment & Development Coordinator at Autism Spectrum Connections Cymru, started by explaining that autism is defined as a developmental difference that is characterised by difficulties with social communication and social interactions and restricted patterns of behaviour, interests and activities.

As the name implies, autism can manifest in a wide range of different ways. It is a lifelong condition experienced by one in 66 people and is often diagnosed in adult life. The prevalence of AS is apparently four times higher in males than in females – but this may not accurately reflect the ratio in the population because women may be better at disguising the condition. AS people often are perceived as being needy, inflexible or pedantic – but as Samuels explained, these apparent characteristics reflect how AS people experience and cope with the neurotypical-based world in which we all live.

Starting point

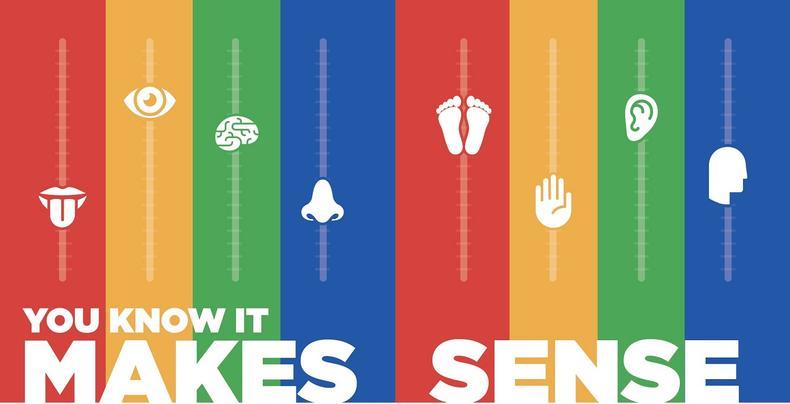

The starting point to understand the AS experience is our senses. In addition to the usual five (visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory and tactile), in the main, people also have three others that are often overlooked:

• Proprioception – the sense of movement and spatial awareness (for example, when you move an arm with your eyes closed, you don’t need to open them to work out where your arm is);

• Vestibular – the sense of balance and spatial orientation; and

• Interoceptive – the sense of the body’s internal stimuli (such as pain, emotion, anxiety and excitement), for example, when the fight-or-flight response heightens other senses.

Most of us have an inbuilt equaliser that balances out our experience of all this sensory input – think of a music producer with lots of sliders that can be moved up and down to achieve a balanced sound. However, AS people often experience sensory input more or less intensely than neurotypical people. This can result in some apparently strange behaviours, such as wearing sunglasses or shaded lenses indoors (in order to tone down visual stimuli) or wearing lots of clothes in summer (in order to increase the tactile stimuli from feeling the weight of the clothes).

Samuels summarised some typical characteristics of AS people. In order to avoid sensory overload, AS people may need to focus on one thing and exclude others: for example, taking in only the verbal communication and blocking out non-verbal aspects. They may not maintain eye contact – but don’t assume that this means that they aren’t listening. They may find hypothetical concepts or abstract thinking difficult and need context. For example, instead of saying “X generally happens”, an AS person would find it easier if you said “X happens approximately 75 per cent of the time”. They may find it difficult to cope with change. Change can lead to anxiety and AS people may experience anxiety differently from neurotypical people. To manage this, AS people often put in place structures, plans and routines. These could be perceived as being inflexible or pedantic, when the underlying reason is not apparent. The importance of not disrupting them – in order to avoid causing anxiety – might not occur to a neurotypical person.

Samuels offered an example of a colleague asking: “Please could I borrow you for a moment?” Most people would understand that to mean: “Have you got a few minutes to talk to me about something?” And you would probably happily reply: “Of course, no problem.” But for an AS person, such a request could be a significant cause of anxiety: it has come out of the blue, with no context or hint of what it might relate to, and moreover, it’s expressed in figurative language.

Adaptations required

Once you have some insight into how AS people experience the world, and provided that you understand that they can’t move themselves into the neurotypical world, it quickly becomes apparent that your normal working practices could be adapted to make things easier for your AS colleagues. For employers, this is a legal requirement of the Equality Act 2010. The Act requires employers to make adjustments for disabled workers in order to make sure that, as far as is reasonable, a disabled worker has the same access to everything that is involved in doing and keeping a job as a non-disabled person.

The practical implications of this were covered by Nik Dowell, the founder of iThink, the UK IPO’s staff neurodiversity network. The network provides colleagues with autism and dyslexia with peer support forums and empowers them to seek changes within the IPO to make it a more autism- and dyslexia-friendly place to work. The network has contributed to a number of awareness-raising initiatives within the IPO and is currently working to improve recruitment procedures for those with autism or dyslexia.

Dowell explained the benefits of having AS people working at the IPO. In addition to the advantages that having a diverse workforce brings in general, AS people typically have skills that are well-suited to the IP professions, such as a STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) background, good attention to detail and being happy to work independently.

Dowell explained the types of adjustments that the IPO has made for its AS colleagues. For example, it endeavours to:

• Use written communication. An AS colleague may find it easier to receive an email than a phone call.

• Be literal and specific (eg say “Nine times out of 10” rather than “usually”) and avoid metaphors or analogies.

• Allow time for the information to be processed and check that the message has been understood – eg follow up a face-to-face discussion or meeting with a written summary by email.

• Make “unwritten” workplace rules explicit rather than assuming that AS colleagues will pick up on them.

• Avoid disrupting routines – AS colleagues may find it difficult to do things at the drop of a hat.

• Manage change carefully – give as much advance warning as possible and provide an explanation and context for it.

• Think about where AS colleagues sit: are they close to a window which gets bright sunlight? Is there a blind so that they can adjust the light? Are they near a door or a walkway that could be a source of disturbance? They may find hot-desking very difficult, so can you let them have their own space?

• Provide quiet spaces (or at least noise-cancelling headphones).

• Adjust targets; help AS colleagues to analyse the job, for example, by breaking tasks down into smaller sub-tasks.

• Allow flexibility in timing of work hours; for example, heavy traffic may be a source of anxiety for AS colleagues.

• Provide training for neurotypical colleagues so they can become allies.

Jonathan Andrews, a trainee IP solicitor at Reed Smith, shared his personal experiences as a legal professional on the autism spectrum. Andrews doesn’t view AS as something that holds him back – it’s just part of who he is. He disclosed his condition to his employer and has been explicit about how it affects him and the traits that it brings. He backed up Dowell’s experience that the adjustments required for AS people are “soft” – not major, and generally easy to make – for example, he requested to visit the room in which he was going to be interviewed beforehand, so that he knew what to expect.

Easy adjustments

The key take-home message for me was that typical adjustments are very practical, easily attainable in most workplaces, and not costly to make – in other words, they are certainly reasonable. However, they could have a huge impact on an AS person, thus enabling them to thrive in the working environment. It really struck me that this is a clear example of people who have a condition that does not make them inherently any less able than others to perform a job, but who could easily be “disabled” by society failing to understand their needs and make simple, practical adjustments for them.

Find out more from the previous IP Inclusive webinar here.